A History of Kentucky’s Funeral Traditions

Kentucky, a state rich in history and folklore, holds a unique and poignant story in its funeral traditions. The journey from rugged pioneer burials to the formalized, modern funeral services of today reflects not only the state’s development but also the deep-seated cultural values of its people. This article explores the evolution of death rituals in the Commonwealth, from the earliest community-led customs to the rise of professional funeral directors and the contemporary choices available to families.

The Pioneer and Community-Led Era

(18th – 19th Centuries)

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, death in Kentucky was a deeply personal and community-centric event. With no formal funeral industry, the responsibilities of preparing the deceased and providing comfort to the grieving fell squarely on the shoulders of family, friends, and neighbors. These were times of hardship, and death was an ever-present reality, often due to disease, accidents, or the challenges of frontier life.

The rituals were simple yet profound. A death in the community would be announced by word of mouth, or sometimes by a church bell tolling a specific number of times, each toll representing a year of the deceased’s life. The body was typically “laid out” at home, a ritualistic practice that involved preparing the body for burial. Family members and neighbors would wash and dress the deceased, and then place them on a “cooling board”—often a simple wooden plank or even a door removed from its hinges—covered with a sheet. A cloth might be tied around the head to keep the mouth from falling open, and coins were sometimes placed on the eyes. The “laying out” process was a communal act of respect and grief.

A central element of these early traditions was the “death watch” or “wake.” For several days and nights, the body would be watched over by friends and family. This vigil served both a practical purpose—preventing animals from disturbing the body and ensuring that the deceased was, in fact, dead—and a social one. Neighbors would bring food, share stories, and offer comfort, transforming the house of mourning into a hub of communal support. The casket itself was often handmade by a local carpenter or a member of the family.

Burial was equally a community affair. Gravediggers, typically men from the community, would prepare the plot, often in a family cemetery on a hilltop or in a churchyard. This practice led to the proliferation of small, family burial plots that dot the Kentucky landscape to this day. The graves were often marked with simple, hand-hewn stones. One peculiar burial tradition, particularly in the Cumberland Plateau region, involved the use of dry-laid stone crypts or cairns to enclose the coffin, a practice that reflected a folk cemetery tradition brought by pioneers.

The Rise of the Undertaker

(Late 19th – Early 20th Centuries)

As Kentucky became more settled and towns grew, the practice of a professional “undertaker” began to emerge. These individuals, often carpenters or cabinet makers who already had the skills to build coffins, started offering additional services, like transporting the body and preparing it for burial. The term “undertaker” came from their role in “undertaking” the arrangements of a funeral.

Embalming, a practice that gained popularity after the Civil War, was a major turning point. Before, bodies were often buried quickly, especially in warmer months. Embalming allowed for longer visitations and the transportation of bodies over greater distances. Early embalmers in Kentucky would often travel to the deceased’s home to perform the service, a practice that continued for some time even after funeral homes became more common. Men like Edward C. Pearson in Louisville were pioneers in this field, with Pearson holding Kentucky’s first embalmer’s license. In 1882, a number of undertakers came together to formally organize Kentucky’s State Association of Undertakers, electing George N. Lynch as its president. The formation of the Undertakers Association was only open to white men. In 1924, the African American community in Kentucky formed the Independent National Funeral Directors Association, later called the National Funeral Directors and Morticians Association. In 1904, to “provide for the better protection of life and health and to prevent the spread of contagious diseases,” the Kentucky State Board of Embalming was formed by the Kentucky General Assembly. State legislators didn’t amend the existing laws until 1914 to include a requirement for licensure of undertakers as well. The creation of institutions like the Kentucky School of Embalming, established in 1895, further professionalized the industry, moving it away from a craft and towards a regulated, specialized trade.

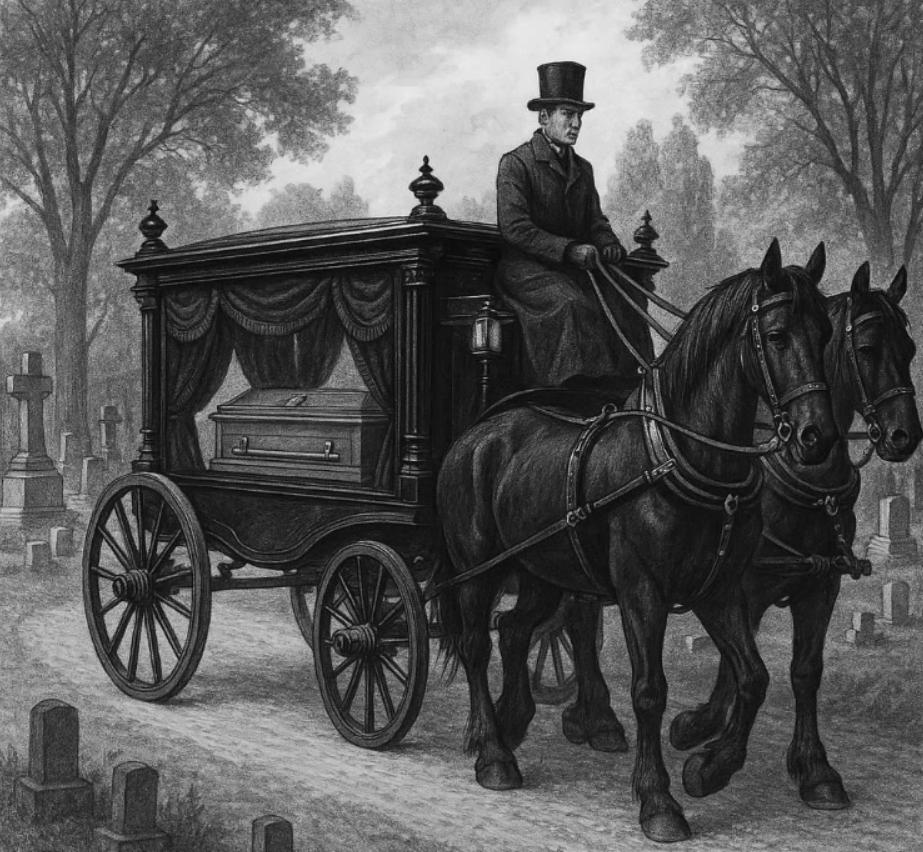

The shift from the home to the funeral parlor was gradual but significant. Early funeral parlors were often attached to a family’s residence, with the embalming room and casket selection area at the back. These businesses, such as the Muster Funeral Homes, which trace their roots to a carpenter building caskets in the 1850s, became pillars of their communities. They began offering not just caskets and embalming, but also hearses (initially horse-drawn), limousines, and a place for the wake and service.

Modernization and Changing Traditions

(Mid-20th Century to Present)

The mid-20th century saw the funeral industry in Kentucky, as in the rest of the nation, become highly streamlined and commercialized. Modern funeral homes, equipped with chapels, visitation rooms, and professional staff, became the standard. This shift removed much of the burden from the grieving family, but it also centralized the process, changing the communal dynamic.

One of the most notable changes in modern Kentucky funeral history is the growing acceptance of cremation. Historically, in a state with strong religious and agricultural roots, burial was the dominant choice. However, in recent decades, cremation rates have risen dramatically. This trend is driven by a number of factors, including lower cost, environmental concerns, and a greater desire for personalized memorial services. Modern Kentucky law allows for cremated remains to be scattered on private property or in designated areas, providing families with more options for final disposition.

The role of technology has also played a part, from online obituaries and virtual guest books to live-streamed funeral services, allowing loved ones to pay their respects regardless of geographic distance. Despite these modernizations, many of the old traditions persist, especially in rural and Appalachian Kentucky. “Family night” viewings at the funeral home remain a common ritual, as do large, comforting “funeral dinners” provided by the deceased’s church or community. The phrase “she made such a purdy corpse,” once a compliment in times when a family’s skill in laying out a body was a point of pride, still echoes in some communities, a testament to the lingering respect for the departed.

A Legacy of Respect and Community

From the simple, handmade caskets and community-dug graves of the frontier to the modern funeral home with its array of services, the history of funerals in Kentucky is a testament to change and continuity. The core values of respect for the dead, comfort for the living, and the central role of community have remained consistent, even as the methods of mourning have evolved. Today, Kentucky’s funeral homes blend traditional dignity with modern convenience, offering a wide range of choices to honor a life lived in the Bluegrass State. The legacy of its funeral traditions is one of resilience, a deep sense of place, and a shared commitment to caring for one another in life and in death.

Funeral Customs and Folklore in Kentucky

Profiles in Kentucky Funeral and Embalming History

Gallery of Funeral Homes

Funeral History Resource Library

Funeral and Embalming Education in Kentucky

Contributed by Shawn Logan | contact@kyhi.org

⁘ Works Cited ⁘

- Alvey, R. G. (1989). Kentucky Folklore. University Press of Kentucky.

- Conner, Niceley, J. “The Kentucky Way of Death: A History of the Development of Mortuary Law in Kentucky.” Master’s Thesis, Eastern Kentucky University 2007:4–12.

- McDaniel (McGuire), Sue Lynn. (1993). Parting Friends: Southeastern Kentucky Funeral Customs. 1880-1915. The Filson Club History Quarterly, 67 (1), 44-67.

- Montell, W. L. (2009). Tales from Kentucky Funeral Homes. University Press of Kentucky.

- Stone, S. L. (1987). Blessed Are They That Mourn: Expressions of Grief in South Central Kentucky, 1870-1910. The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society, 85(3), 213–236.

- The Courier-Journal, Louisville, Kentucky, 2 March 1882

- Wilson, C. R. (1983). The Southern Funeral Director: Managing Death in the New South. The Georgia Historical Quarterly, 67(1), 49–69.

Important note:

If you would like to use any information on this website (including text, bios, photos and any other information) we encourage you to contact us. We do not own all of the materials on this website/blog. Many of these materials are courtesy of other sources and the original copyright holders retain all applicable rights under the law. Please remember that information contained on this site, authored/owned by KHI, is provided under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Photographs, text, illustrations and all other media not authored by KHI belong to their respective authors/owners/copyright holders and are used here for educational purposes only under Title 17 U.S. Code § 107.