The Kentucky Home Society for Colored Children, though a lesser-known institution in the broader narrative of American philanthropy and social welfare, played a significant role in the lives of countless African American children in Kentucky during the early 20th century. Established in 1909 in Louisville, Kentucky, this organization emerged from a critical need within the Black community for structured care and support for orphaned, abandoned, or “hard to place” children during an era of profound racial segregation and systemic inequality. Its history, purpose, and eventual reorganization reflect both the dedicated efforts of Black leaders to uplift their communities and the inherent challenges posed by a racially divided society.

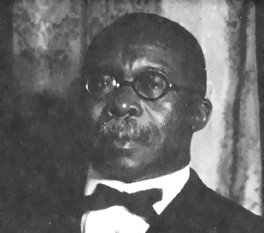

The founding of the Kentucky Home Society for Colored Children was spearheaded by prominent African American figures, most notably Charles Henry Parrish, Sr. Initially, Rev. Octavius Singleton served as superintendent, but Parrish quickly took the helm, guiding the institution through its formative years. The establishment of such a home was a direct response to the lack of adequate state-provided services for Black children, who were often overlooked or marginalized by mainstream welfare systems. In a society where racial discrimination was institutionalized, Black communities were compelled to create their own support networks and organizations to address the pressing social needs of their members. The Kentucky Home Society for Colored Children was a testament to this self-reliance and communal solidarity.

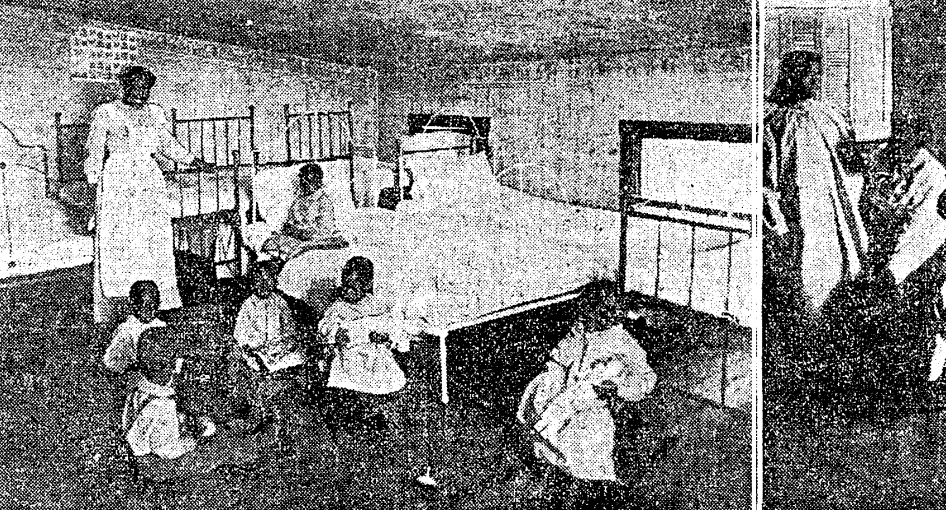

The primary purpose of the Kentucky Home Society for Colored Children was to provide shelter, care, and a semblance of stability for vulnerable Black children. These children, often described as “defective” or “hard to place” by the societal standards of the time, found a refuge within the Home. The main facility was located at 825 S. Sixth Street in Louisville, with additional children housed in buildings at the former Eckstein Norton school in Cane Spring, Kentucky. Beyond basic sustenance and shelter, the institution aimed to offer an environment where children could be nurtured, educated, and prepared for adulthood, though the specifics of their educational and vocational training are not extensively detailed in available records. The goal was to equip these young individuals with the skills and character necessary to navigate a challenging world, fostering their development into productive members of society.

From its inception, the Kentucky Home Society for Colored Children sought financial support to sustain its operations. In 1910, the Kentucky General Assembly passed an act that provided an annual sum of five thousand dollars to the organization. This state funding was crucial for the Home’s survival and expansion, reflecting a degree of recognition, albeit limited, from the state government regarding the critical services the institution provided. The state’s commitment grew over time, with the annual allocation increasing to $10,000 in 1912 and further to $15,000 by 1920. This financial support allowed the Home to care for a larger number of children and, presumably, improve its facilities and services.

Despite the vital role it played, the Kentucky Home Society for Colored Children faced significant challenges throughout its existence. The care of the children and the condition of the facilities were frequently subjects of scrutiny and concern. It is plausible that, like many institutions of its kind during that era, it struggled with limited resources, overcrowding, and the inherent difficulties of caring for a diverse group of children with varying needs. The societal prejudices of the time also meant that Black institutions often received less funding and attention compared to their white counterparts, making it an uphill battle to maintain high standards of care. The very description of some children as “defective” highlights the prevailing discriminatory attitudes that permeated even welfare efforts.

A notable figure associated with the Home was Bessie Allen, who managed the Sixth Street location at some point. The blues singer Mary Ann Fisher was also one of the children who resided at the orphanage, offering a glimpse into the lives of individuals who passed through its doors. These personal connections underscore the human impact of the institution, providing a tangible link to the children it served.

The trajectory of the Kentucky Home Society for Colored Children took a significant turn in 1937 when state funding was withdrawn. This withdrawal marked a pivotal moment, leading to the reorganization of the Home Society. The children under its care were subsequently removed and placed in boarding homes, with their oversight shifting to a state-employed supervisor. This change coincided with the development of a newly created section for “Colored children” within the Division of Child Welfare of the State Department of Welfare. This transition suggests a move towards a more centralized, state-controlled approach to child welfare, even as racial segregation persisted within these governmental structures.

The reorganization prompted further examination of the resources available for Black children in Kentucky. In 1938, a consultant from the Children’s Bureau of the U.S. Department of Labor was brought in to conduct a study of these resources. This was followed by a conference of representative Negro citizens in Louisville, convened to discuss the findings of the study. These efforts indicate a growing awareness, both at the state and federal levels, of the disparities in child welfare services for African American children and the need for more structured and equitable provisions.

It is important to distinguish the Kentucky Home Society for Colored Children from other similar organizations that emerged during this period. For instance, the National Home Finding Society for Colored Children, founded by Rev. O. S. Singleton (who had briefly been involved with the Kentucky Home Society), operated independently with no state affiliation, relying primarily on donations and fundraising. While both aimed to serve Black children, their operational models and funding sources differed, highlighting the diverse approaches adopted by Black communities to address systemic neglect.

In conclusion, the Kentucky Home Society for Colored Children stands as a testament to the resilience and self-determination of the African American community in Kentucky during an era of profound racial inequality. Founded by Black leaders like Charles Henry Parrish, Sr., it provided a crucial haven for vulnerable children, offering them care and a chance at a better future. While it faced persistent challenges related to funding, facilities, and societal prejudices, its existence, state support, and eventual reorganization reflect a complex interplay of community initiative and evolving state welfare policies. The Home’s story is a vital part of the broader narrative of African American history in Kentucky, illustrating the enduring efforts to create institutions that fostered well-being and opportunity in the face of systemic discrimination. Its legacy lies not only in the tangible care it provided but also in its representation of a community’s unwavering commitment to its youngest and most vulnerable members.

Contributed by Shawn Logan | contact@kyhi.org

⁘ Works Cited ⁘

- Slingerland, W. H. Child Welfare Work in Louisville: A Study of Conditions, Agencies and Institutions. The Welfare League of Louisville. April, 1919.

- Kentucky Home Society for Colored Children (Louisville, Kentucky), Notable Kentucky African American Database, University of Kentucky.

- The Courier-Journal, Louisville, Kentucky, 9 July 1909

- The Courier-Journal, Louisville, Kentucky, 6 August 1911

- Kentucky Commission on Human Rights

Important note:

If you would like to use any information on this website (including text, bios, photos and any other information) we encourage you to contact us. We do not own all of the materials on this website/blog. Many of these materials are courtesy of other sources and the original copyright holders retain all applicable rights under the law. Please remember that information contained on this site, authored/owned by KHI, is provided under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Photographs, text, illustrations and all other media not authored by KHI belong to their respective authors/owners/copyright holders and are used here for educational purposes only under Title 17 U.S. Code § 107.