Early Beginnings

Note: this page is a work in progress and additional information and photos will be added. If you have photos or stories you’d like to share, let us know!

The Miners Memorial Hospital Association, in part, was the grand dream of US labor leader John L. Lewis. Lewis, though not without the occasional controversy, was an ardent defender and advocate for coal miners’ rights. From leading strikes for better wages to demanding safer working environments, Lewis was a figure to be reckoned with. He worked with President Franklin D. Roosevelt during the New Deal to advocate for labor rights. For four decades, Lewis was president of the United Mine Workers of America until his retirement in 1960. The “bristling, bushy-eyebrowed” behemoth was, according to some, soft-spoken and had a dynamic personality.

Appalachian life was rough and jobs were often scarce. Coal was a natural resource that many depended upon exclusively to help provide for their families. With the voice and prowess of John Lewis and many others, the Appalachian coalfields began filling with hospitals; from Beckley, West Virginia to Middlesboro, Kentucky. These unique hospitals provided high-quality medical care to miners, surviving near-misses of financial disaster, issues within the established medical community, and scattered storms of local politics.

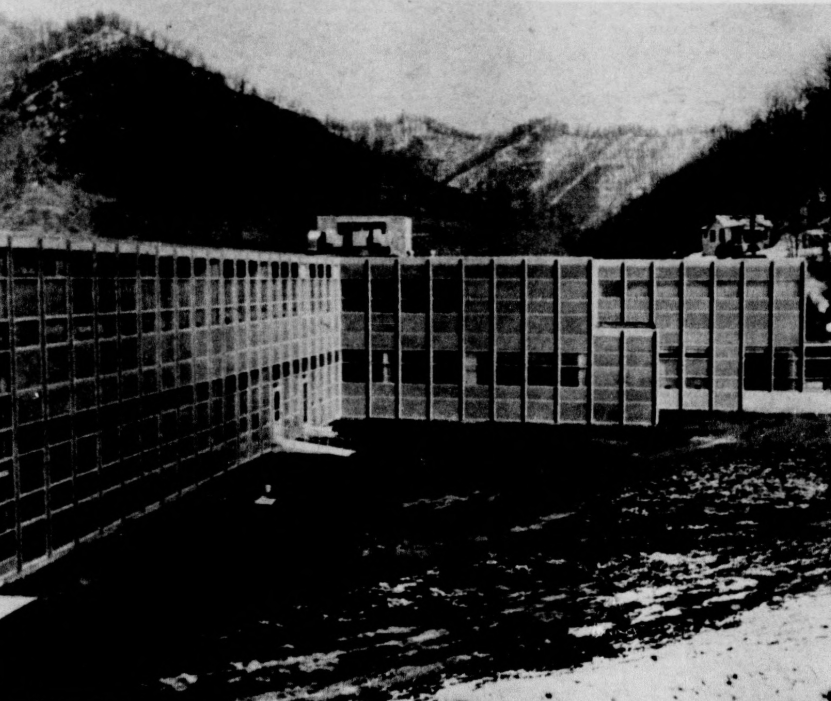

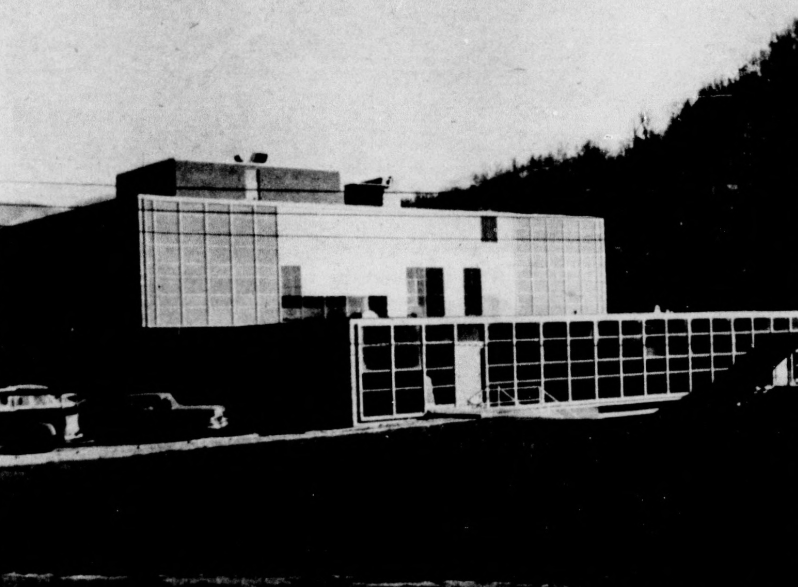

The United Mine Workers, utilizing funding from a rather massive purse of the Welfare and Retirement Fund of the UMW, established ten hospitals. In Kentucky those included Hazard, Whitesburg, Harlan, Middlesboro, McDowell, Pikeville, and South Williamson. There were also hospitals at Wise, Virginia, and Beckley and Man, West Virginia. The UMW was able to fund these hospitals with state-of-the-art equipment, often times better than any of these Appalachian communities had ever seen before. All of that equipment and facilities were little without competent staff; the UMW would often search country-wide for physicians, nurses, and technicians paying them “handsome salaries” to encourage them to remote Appalachia. However, this was not without controversy as established mountain physicians and private hospital proprietors were quite vocal about having salaried physicians in what many considered “socialized medicine.” Newspaper reports often cited that these physicians, “were offended by the presence of salaried doctors, union hospitals and outsiders’ interferences with the way medical things had always been done.”

Nevertheless, physicians were slowly credentialed to practice (though this was often hampered when possible; the Commonwealth went as far as trying to prohibit out-of-state physicians or medical providers though legislation failed). For about a decade, a UMW miner or his family could present their medical card to get “serious medical attention and competent care.” Reports, however, revealed that union corruption and an increase in non-union strip mines made significant cuts into the UMW’s Welfare and Retirement Fund. A decrease in funding availability and an increase in operating costs for the hospitals meant that the Miners Memorial Hospital Association was at risk of being permanently closed, a short ten years after its inception. As such, The Association announced that the hospitals were up for sale.

The Beds and Costs of the UMW Hospitals in 1956

| Hospital | Beds | Cost per sq. ft. | Cost per bed |

| Beckley | 190 | $20.46 | $13,249 |

| Man | 80 | 25.05 | 17,375 |

| South Williamson | 140 | 22.79 | 14,786 |

| Pikeville | 50 | 26.54 | 22,158 |

| McDowell | 60 | 27.61 | 19,358 |

| Hazard | 90 | 24.33 | 17,497 |

| Whitesburg | 90 | 23.16 | 18,070 |

| Wise | 60 | 25.13 | 19,554 |

| Middlesboro | 80 | 23.80 | 18,177 |

| Harlan | 200 | 19.25 | 12,852 |

School of Professional Nursing and Other Educational Ventures

During the Summer of 1957, the Miners Memorial Hospital Association began completing its steps to opening a professional school of nursing located in Harlan, Kentucky and as part of its network. The goal was to, “educate professional nurses for the ten Memorial Hospitals which provide[d] services for beneficiaries of the United Mine Workers Welfare and Retirement Fund.” By 1957, six classes of practical nurses had already been trained for duty within the hospital network.

In June of 1957 prospective male and female applicants for the Harlan school began the interviewing process. Prerequisites required applicants to have a high school diploma, be between the ages of 17-35, and to pass the entrance requirements set forth by Morehead State College, Morehead, Kentucky, where first-year students would be enrolled. The program leading to a diploma in nursing and registration in Kentucky as a professional nurse required three years.

The first two semesters would see students enrolled in Morehead State College coursework which included human anatomy and physiology, general chemistry, nutrition, microbiology, psychology, sociology, English, and physical education. For the remaining three years, students would spend time in the Miners Memorial Hospital Associations facilities gaining clinical experience in medical, surgical, pediatric, and obstetrical nursing. Additionally, psychiatric training was offered in partnership with Kentucky State Hospital. Miss Irene Healy was the Director of the School of Professional Nursing.

The first class to graduate from the Miners Memorial Hospital Association School of Professional Nursing received their diplomas and pins September 14, 1960. The ceremonies took place in the auditorium of the Harlan High School and included thirteen young women and three young men. All students were from Kentucky, West Virginia, or Virginia high schools with most of them being from the Appalachian mountain region. Nearly half of the first class previously worked non-professional jobs before starting their nursing careers.

Other Educational Ventures

- School of Professional Nursing, Harlan, Kentucky

- School of Practical Nursing, Williamson, West Virginia

- School of Medical Technology, Beckley, West Virginia

- School for Nurse Anesthetists, Harlan, Kentucky

New Beginnings

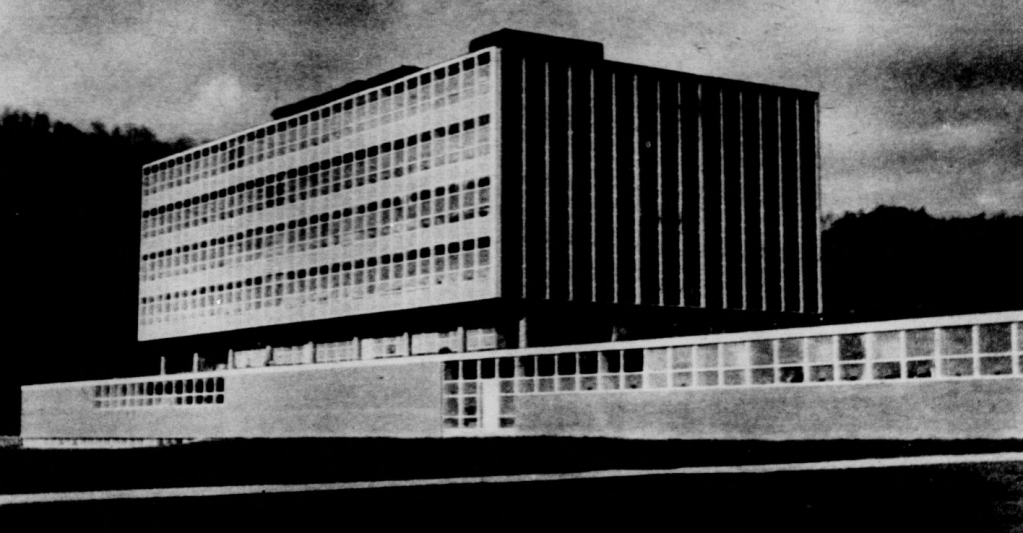

Locals became increasingly worried that they would lose access to healthcare they had only dreamed of before. The Board of National Missions of the US Presbyterian Church and Kentucky Governor Bert Combs established an independent, non-denominational, non-profit corporation to purchase and operate the Miners Memorial Hospital Association facilities in 1963. It was at this time that the newly formed corporation, Appalachian Regional Hospitals, Inc., purchase the hospitals for a sum of $8 million dollars–a fraction of the original cost to build the hospitals.

Such as life often is, the newly formed Appalachian Regional Hospitals, Inc. began facing difficulties upon its opening. This happened in October in 1963 when the doors “reopened” to the public–not only mining families but entire regions of mountain towns and countryside, they soon realized that they, “owned not a penny of operating funds.” Fontaine Banks noted that, “the cash registers were empty.” Though congress permitted taxpayer funding, this was still not enough. Additionally, the newly formed corporation would need to acquire funding from the federal government and private foundations in order to continue operations. They also faced a new challenge: these hospitals previously served miners and their families, now the doors were open to everyone. That meant that they had to compete with existing hospitals and facilities–including those that previous mountain physicians fought so hard against.

Shortly thereafter, the federal government and other resources refused funding to two community hospitals in the same small town. The logical response would be a merger but this became muddied and incredibly unclear. In Pikeville, Kentucky, ARH, Inc. turned over the hospital and its debts to the Methodists who already had established a hospital in town. Newspaper reports that then president or ARH, Inc. T. P. Hipkens said the decision to turn over the hospital was regrettable but for reasons that were never fully clear.

The Hospital in Hazard was not without controversy either; the existing Mountmary Hospital, operated by Catholic nuns, caused many in the town to split; some wanted ARH, Inc. to be a part of their local community while others were very vocal about allowing the order of Catholic nuns to continue operating Mountmary Hospital. In the end, ARH, Inc. won that battle but it left a sour taste with many local residents.

The hospitals that John L. Lewis had dreamed of, though hitting many roadblocks, slowly began flourishing. Many expanded their facilities and services and maintained a reasonably sound financial condition. ARH, Inc. began seeing itself as a sort of pioneer in bringing healthcare to Appalachians at a reasonable cost. This was generally done so through centralization of hospitals’ non-service-related function (e.g. payroll and supply purchasing) and decentralizing service functions, such as prevention and treatment of disease. In the 1970s, the government, via the Appalachian Regional Commission, provided 80% of the funding for all of the ARH, Inc. new construction and medical projects. The federal government also purchased 25% of the chain’s services via Medicare and the Commonwealth paid for 25% via Medicaid. Hospital bills of miners were paid by contract via the Welfare and Retirement Fund, accounting for about 30%. Private insurers, workman’s compensation, and vocational rehabilitation services accounted for about 10%. As with many hospitals in today’s world, fears of finding funding and continuing operations were always at the forefront.

The role of community hospital would soon advance into headquarters for smaller clinics and home-care teams; these teams would “roam the creeks and hollow in four-wheel drive vehicles, treating patients in their homes.” In the early 1970s, six outpost clinics were established in Kentucky and West Virginia, with at least one physician, nurse, and sometimes a social worker or nutritionist. Other “enterprises” were in association with local physicians in group practices.

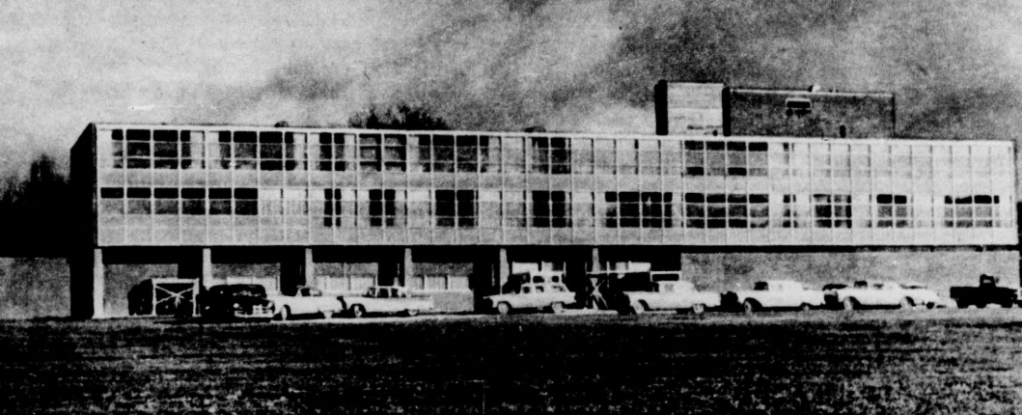

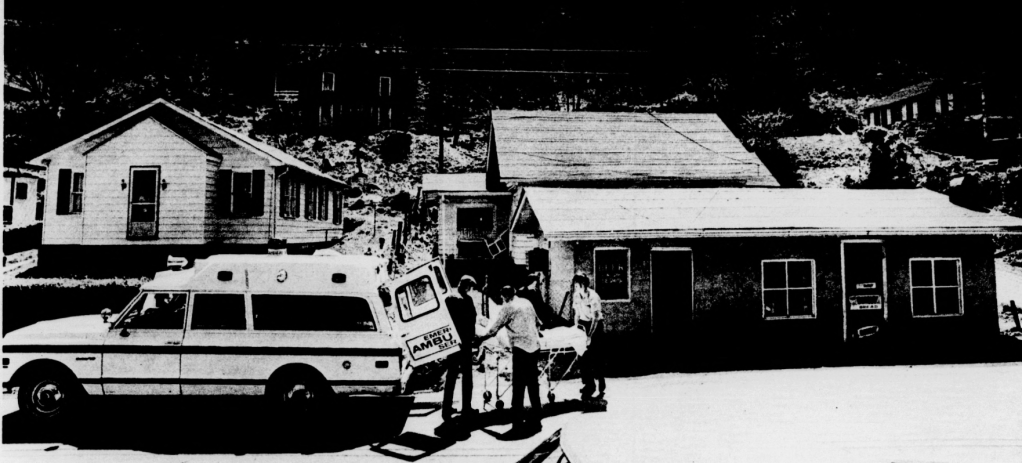

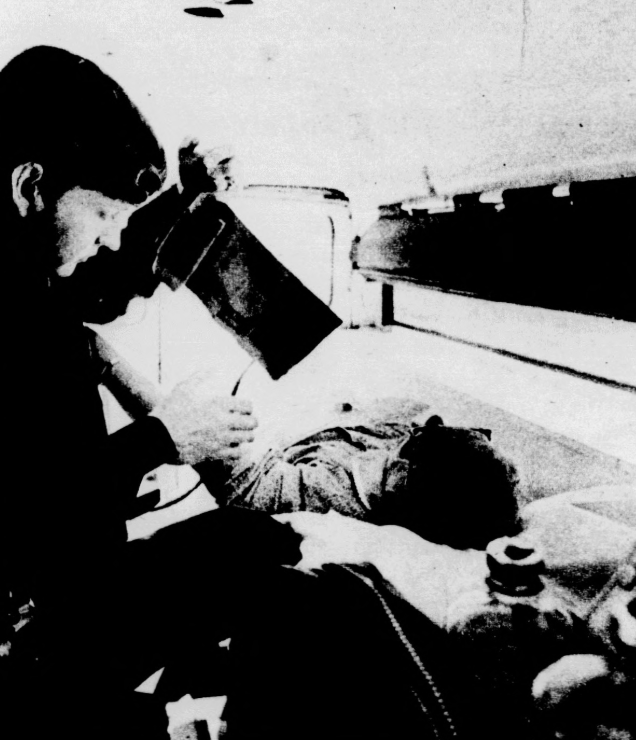

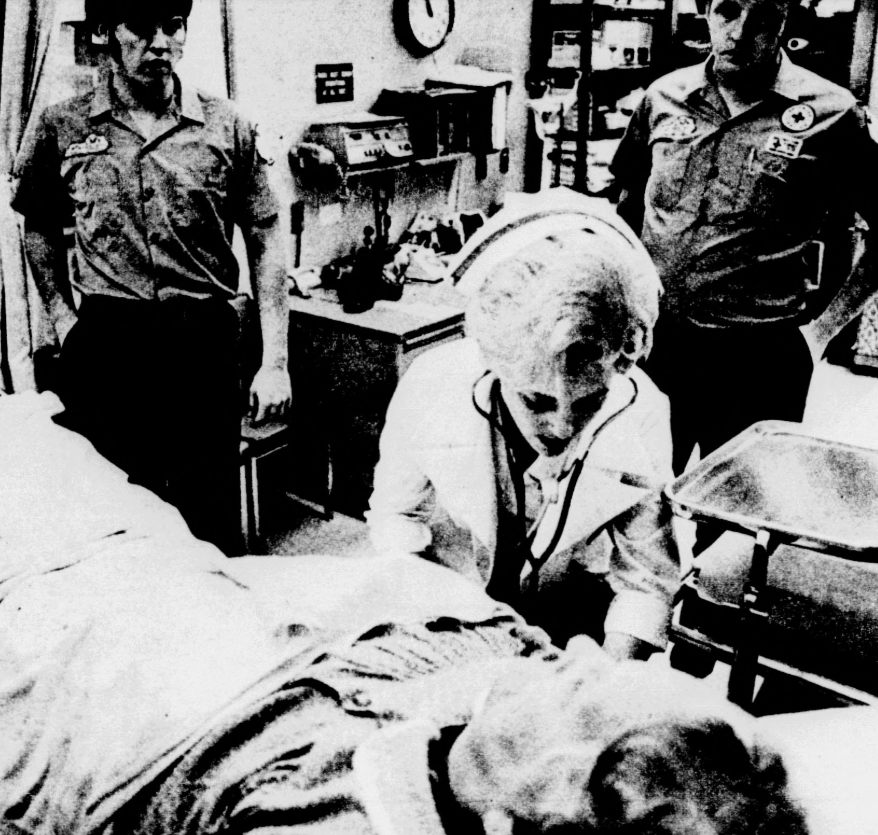

Appalachian Regional Hospitals, Inc. operated an eight-county ambulance service with a home-base at the ARH Hazard where trained attendants could reach into the hills to service more people in Eastern Kentucky. Pictured is an ambulance transporting a sick elderly woman from her home to the emergency room in Hazard.

To view photographs of the Man Miners Memorial Hospital (part of the MMHA network), AbandonedOnline has agreed to allows us to link to their website. You can visit them at:

AbandonedOnline.net

Contributed by Shawn Logan | contact@kyhi.org

⁘ Works Cited ⁘

- The Courier-Journal, Louisville, Kentucky 15 January 1956

- Floyd County Times, Prestonsburg, Kentucky, 13 June 1957

- Danville Advocate-Messenger, Danville, Kentucky, 22 April 1960

- The Advocate-Messenger, Danville, Kentucky, 2 September 1960

- The Courier-Journal & Times, Louisville, Kentucky, 15 June 1969

- The Courier-Journal, Louisville, Kentucky 24 June 1973

- Mulcahy, Richard. “Health Care in the Coal Fields: The Miners Memorial Hospital Association.” The Historian 55, no. 4 (1993): 641–56.

- Mulcahy, Richard. “A New Deal For Coal Miners: The UMWA Welfare and Retirement Fund and the Reorganization of Health Care In Appalachia.” Journal of Appalachian Studies 2, no. 1 (1996): 29–52.

Important note:

If you would like to use any information on this website (including text, bios, photos and any other information) we encourage you to contact us. We do not own all of the materials on this website/blog. Many of these materials are courtesy of other sources and the original copyright holders retain all applicable rights under the law. Please remember that information contained on this site, authored/owned by KHI, is provided under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Photographs, text, illustrations and all other media not authored by KHI belong to their respective authors/owners/copyright holders and are used here for educational purposes only under Title 17 U.S. Code § 107.